There’s a face-off at the Huntington Museum of Art near Los Angeles. The contenders are Thomas Gainsborough’s 18th-century painting Blue Boy and Kehinde Wiley’s very 21st-century Portrait of a Young Gentleman. The two young men are sportily dressed and look directly at visitors; they even stand the same way. But there is one major difference.

They remind me of trading cards. Today’s cards show baseball and football heroes. In my day we traded pictures of artworks. The most coveted card was “Blue Boy.” A really cute fellow a bit older than we were — with a spiffy blue satiny suit, blue bows on his silky brown shoes, and a big hat with a flowing feather on it. Adorable!

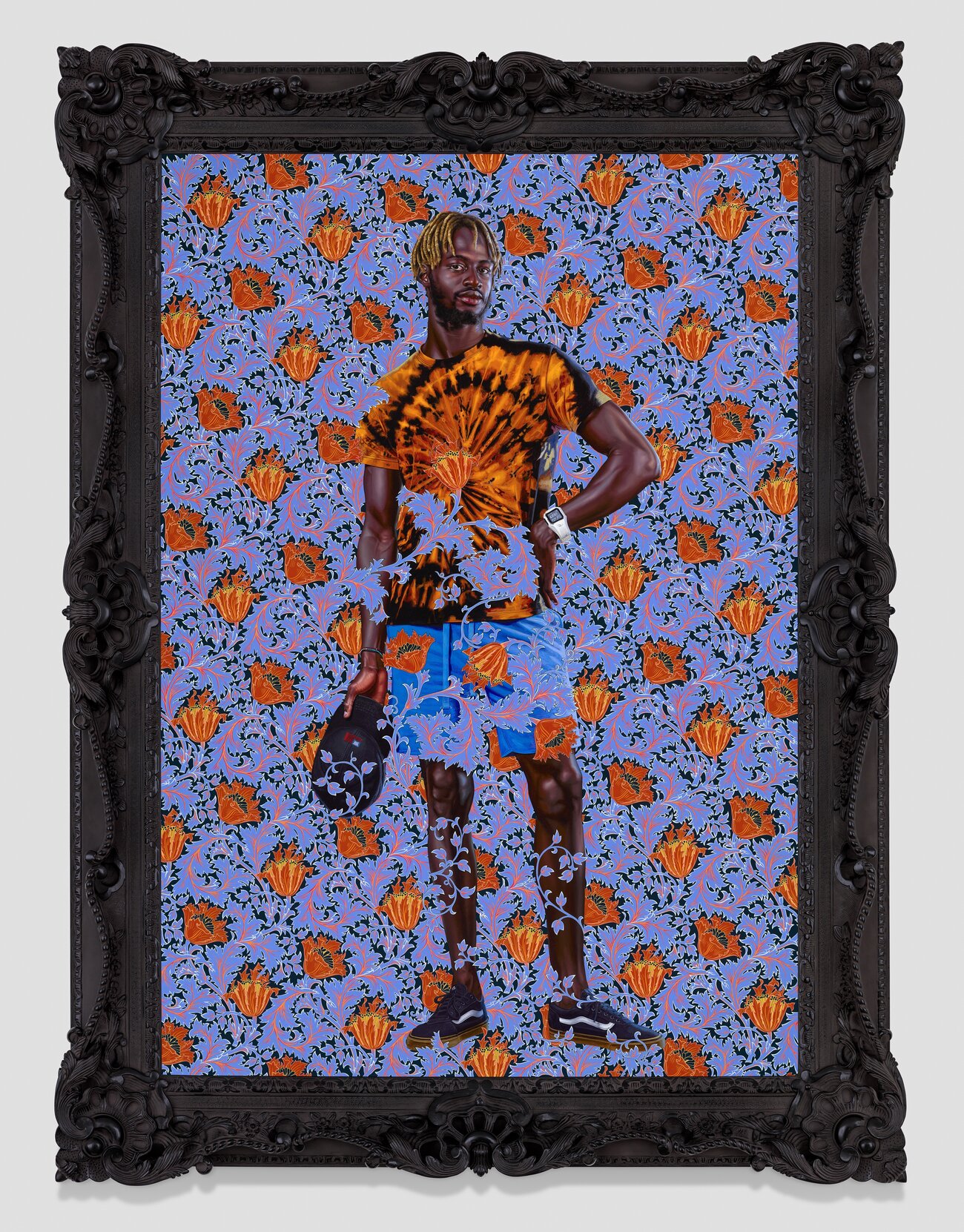

This year marks the hundredth anniversary of the year Henry and Arabella Huntington, the institution’s founders, bought the painting. To celebrate the centennial, Nielsen got the idea to commission Wiley, the African American artist who painted President Obama’s official portrait, to respond to Gainsborough’s wealthy white boy. Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of a Young Gentleman hangs across the room from Blue Boy. Same size. Same pose — left hand on hip. Same ornate frame (except the frame is painted black).

“Here, I’m trying,” Wiley explains, “to allow for even the presentation of the painting to take on the nature of its meaning.”

I have a place here, the frame signals. I look different. And I belong. Wiley’s young Black man is turned out in hip 21st century fashion. He wears blue and orange shorts and a psychedelic orange t-shirt, carries a baseball cap, and his short dreadlocks have dyed blonde tips. “A little bit hippie, a little bit hobo, a little bit surfer bum” Wiley says. (I think he’s better dressed than Blue Boy.)

Growing up, Wiley came to the Huntington very often, and loved looking at portraits from earlier centuries. But he never saw people who looked like him on the walls. There was an exception: He was the same age as Gainsborough’s boy, and that was a draw.

“Looking at Blue Boy was something of an escape from seeing all the stodgy adult pictures,” he says.

In his elegant and detailed work, Kehinde Wiley shows how Western European painting can be reimagined to, his words, “be more inclusive.” He uses Old Master techniques to present his very 21st-century people. Curator Christina Nielsen thinks Wiley draws a straight line through the history of art. He “really shows that contemporary art is on a continuum with the past,” she says.

Across the centuries, Wiley’s surfer dude and Gainsborough’s Blue Boy are both in a state of becoming. They’re young men “right on the cusp of adulthood.”

Hanging across from one another at the Huntington, each reflects the values of his day — what their cultures celebrate, what they say “yes” to. Wiley calls it a facedown. “Squaring off. But nothing’s resolved.”

It’s up to viewers to decide how to contend with the past, and how to look at a more inclusive presence — in life and in apposition, on the walls of a distinguished art institution. And Wiley has some hopes. “There’s a bit of optimism here, but also a cautionary tale about inclusion and being able to open up the doors of these museums to more voices like this.”

Kehinde Wiley, Thomas Gainsborough and their youthful models, offering ideas — and beauty — in San Marino, California.